By Paul Richardson

The era of the great road races in Europe where the high pitched song of racing engines could be heard resounding through the streets of cities, towns, and sleepy mountain villages is long gone. Races like the Targa Florio around the island of Sicily and the Mugello Grand Prix near Florence have a ring to their name and are synonymous with truly classic sports car races. But of all road races, the Mille Miglia was probably the most arduous and testing of them all—one in which a works TR2 was to make its racing debut.

So why was the Mille Miglia such a challenge? It was essentially a 1,000-mile sports car Grand Prix, starting and finishing at Brescia, and run over some of the most treacherous roads imaginable, where a mistake on many sections could end up with a trip down a ravine. Even on the fastest sections, where leading cars peeled off mile after mile at 170 mph, the straight roads were often narrow, heavily cambered, and full of nasty surprises—like dozens of hidden brows, notoriously bumpy railway crossings, and dips in the road where faster cars became airborne. There were also those surprise potholes along the loose surfaced edges of the roads, which could burst a tire or damage suspension or chassis.

The high speed sections were tricky enough, but roughly half the race, between Pescara and Bologna, ran through the very twisty climbs and descents of the Apennine Mountains which ended with the Radicofani, Futa, and Raticosa passes south of Bologna. Cars were often literally shaken apart, or their suspension destroyed, if tough sections were taken with too much enthusiasm. A regular problem was the fact that fuel tanks often fractured or broke loose from their mountings due to the constant shock loadings. It must also be remembered that cars had no seat belts in those days, so, bearing in mind that the Mille Miglia was a 1,000-mile race with no letup, untethered drivers and co-drivers were subjected to constant buffeting—especially the co-drivers, who had no steering wheel to hang on to, only a small grab handle on the dash.

The 1954 Mille Miglia saw an entry list of over 470 cars of all types, from out-and-out racing sports cars entered by factory teams to small saloon cars driven by amateur drivers who joined with the professionals to battle for glory in arguably the greatest of all road races. Such was the support by the Italian contingent in 1954 that there were no fewer than 22 Ferraris entered, including works cars for Farina, Paolo Marzotto, Giannino Marzotto, Maglioli, and Biondetti; the works Lancia team consisted of no less than Ascari, Villoresi, Taruffi and Castellotti. British works entries included two Aston Martin DB3s for Reg Parnell and Peter Collins and three Austin-Healeys for Lance Macklin, Louis Chiron, and Tom Wisdom (Macklin and Chiron driving alone).

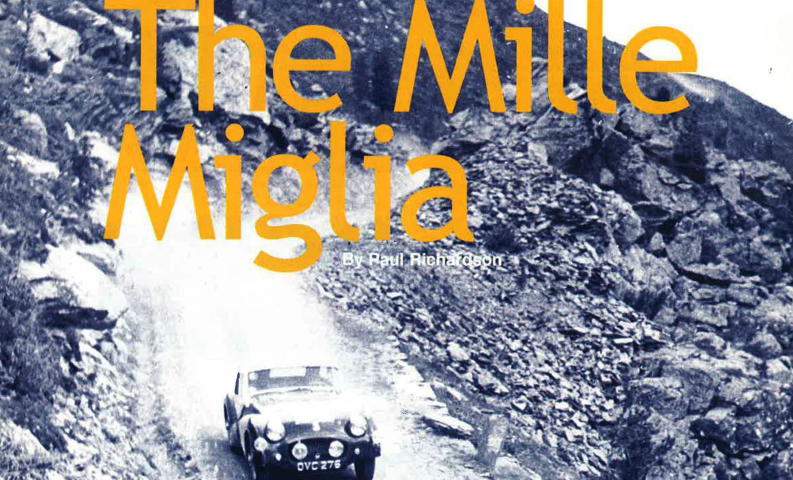

This was also the racing debut for works TR2 OVC 276 for Ken Richardson and Maurice Gatsonides. Ken, who developed the TR2, entered this race specifically to see how the car would perform and stand up to the mechanical stresses of the Mille Miglia prior to starting the Triumph competition department.

Among the host of saloon cars of all types entered, some sported the inevitable “go faster tape,” and probably the most entertaining contingent were the seven Isetta bubble cars entered! I remember driving an Isetta in my youth. It had no reverse gear, and the single door consisted of the whole of the front of the vehicle, which opened forward. If you forgot about the front-opening door and parked too close to the pub wall or parked traffic, you couldn’t get out of the damn thing. As you had no reverse, you either had to shout for help to push the car back, or climb out through the roof light!

Conditions for the 1954 Mille Miglia turned out to be more of a challenge than normal because a particularly harsh winter had further broken up road surfaces, and torrential rain had been flooding Italy for days, bringing with it mist and thick fog. The mixture of intermittent rain, fog, and sudden mists throughout the race led to many car accidents.

Giuseppi Farina, who started the race at 6:06 a.m. in his Ferrari, was to come to grief early in the race. He crashed heavily, breaking his arm, only a few miles from the start near Lake Garda. The race then ran east through Verona, Venice, and Padova, where the route turned south to Ferrara and then southeast to Ravena for the long blast down the Adriatic coastline to Pescara.

It should also be noted here that if the sun were shining, drivers had it full in the face for the first half of the race until they turned west at Pescara to tackle the infamous climbs and descents of the twisty Apennine Mountain passes en route to Rome. This section was notorious for accidents, and Reg Parnell, who was in 5th position at Pescara, had an enormous crash on the Popoli to Aquila section. His Aston Martin was completely destroyed with such an impact that both the engine block and gearbox casings were split—not to mention the chassis. Unfortunately, the other DB3 driven by Peter Collins did not finish either. Aston Martin, like Jaguar, never entered the race again.

My late father said that besides the obvious dangers of the race, the Italian enthusiasts had an unnerving habit of crowding onto the roads in hordes to see approaching cars, only moving back at the last moment when the speeding cars were almost on top of them. This caused several tragic accidents.

The gallant Taruffi set new records down to Pescara in his Lancia and was leading the race at Rome only to crash off the road later when he had to take avoiding action whilst overtaking a slower car. Third-place Castellotti went out before Rome with a failed transmission, leaving Alberto Ascari the sole survivor of the works Lancia team.

In the midfield race, Chiron’s Austin-Healey went out with a fractured brake pipe, and Tom Wisdom’s car suffered a broken valve spring. This left Lance Macklin the sole survivor of the Healey team. He drove a superb race alone in his 2.6-liter Healey, and finished 23rd overall. As well as the single works TR, there were also two privately entered TR2s driven by Les Brooke and Jack Fairman, with Stoddart in the second car. The Brooke TR ran out of fuel, but finished in 64th place, and the Stoddart car crashed.

The race was won by the remarkable Alberto Ascari in a Lancia at an average speed of 87.3 mph, followed by Marzotto in a Ferrari and Musso in a Maserati. Ascari never intended to drive in the race because he hated it. In fact, he insisted that his F1 contract with Lancia stipulated that he would never be asked to drive in the Mille Miglia. He only stepped in at the last moment to take the place of his teammate and idol, Luigi Villoresi, who had been seriously injured while practicing for the race.

The fantastic race-long duel for second place between Paolo Marzotto and Luigi Musso continued through Modena, Parma, Cremona, Mantua, and finally to Brescia. At the finish, Marzotto took second with Musso only a mere nine seconds behind after 12 hours of racing.

Amidst all the drama, mechanical failures, and accidents throughout the race (which that year was dubbed “a mechanical massacre”), the works TR2 of Richardson and Gatsonides ploughed on relentlessly and reliably to finish in a very creditable 27th place overall at an average speed of 73 mph. Thus, the 1954 Mille Miglia was the start of the works TR era, and the TR2 OVC 276 used in that race became Ken Richardson’s personal competition car and went on to win major honors in many European events thereafter. OVC 276, that King of TRs, still survives today and is regularly driven on the open roads of Europe, as if making a statement for the TR’s legendary reputation for stealth and reliability.

It would be remiss of me at this stage not to mention the fact that, of the seven Isetta bubble cars entered, four finished the race, and the car driven by Cipolli and Brioschi won the Index of Performance Award. Cipolli’s race average was 44.8 mph, and the race took him some 20 hours to complete—doubtless flat-out all the way. He then realized that if he drove in the 1955 event alone, to increase the power-to-weight ratio, he might finish with a higher race average than the outright winner of the 1927 race. The indomitable Cipolli achieved his dream.

To conclude, I think it fitting to quote the late Denis Jenkinson, who navigated Stirling Moss to that record-breaking victory in 1955 in a 300SLR Mercedes.

“Jenks” said of the Mille Miglia, “This was not a motor race, this was something far greater, far tougher—it was a battle between the human race and all those things its agile brain had schemed up. Here was man trying to prove to himself that the machines he made, the roads he built, the houses, the walls, the bridges, everything he had constructed, were for his use and that he was the master of them all. Nature was putting up her best opposition, and everything that man had made with his own brain and hands was now conspiring to kill him. If we gave up now, it would be admitting defeat by our own devices. I could see that we must go on, we must fight our way through, this was not a battle of one man against another, it was an impossible fight of man against himself, and if he gave up now, the human race was going to lose some of its reason for existence.”

'The Mille Miglia' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!