By Graham Robson

Like all the best racing drivers that may be listed on betting sites such as 벳엔드, Norman Dewis was a stocky little man. Like all the best racing drivers, he had boundless self-confidence. But although he looked the part, and was as fast as the superstars he befriended at Jaguar, Dewis was not a racing driver. Jaguar’s autocratic boss, Sir William Lyons, saw to that. Dewis, he insisted, was being paid to test and develop cars, not to race them.

Even so, if you’ve ever wondered why legendary Jaguars like the E-Type and the D-Type had small cockpits, look no further than test driver Dewis. Norman, a bustling little turkey-cock of a man, was also Jaguar’s sports car manikin. In those days, new cars often took shape on the workshop floor, with a body shell schemed up around a driver; at Jaguar, Dewis was that man. Which explains why, for years, larger racing drivers like Mike Hawthorn and later, Graham Hill, complained that they could not get comfortable in racing Jaguars.

Legends tend to feed on themselves. Dewis was Jaguar’s chief test driver from 1952 until 1985, when he retired, and his job title told an accurate story. Enthusiasts, however, saw him rubbing shoulders with superstar drivers at Le Mans, saw him make the first test runs—and even heard of him surviving spectacular high-speed crashes in race cars. Here, they thought, was a man with the best job in the world.

But it wasn’t always like that. Most of Dewis’s time was spent patiently driving the new cars, which would provide Jaguar’s bread-and-butter. Much of the time he’d be circulating the test track, checking out mundane things like ride and handling, damper settings, and the latest set of vibration-reducing engine bearers. Here was a man who had driven D-Types at 170mph and beyond, but who also could spend hours at 30, 40 and 50mph, chasing a vibration, a smell or a strange noise. Did you like Jaguar’s choice of ride and handling standards for the XK150, the Mk II, the XJ6, and the E-Type? Along with his boss Bob Knight, it was Dewis who made the final recommendations.

Although his working life at Jaguar included highlights like setting high speed records on the Jabbeke Road in Belgium, setting MIRA lap records in the one-off mid-engined XJ13 and shaking down all the newly-built ‘works’ racing D-Types, it didn’t start out like that. His very first job was in a green -grocer store—60 hours every week, starting at six o’clock every morning. Even so, Coventry-born Dewis always seemed to be close to motor cars. With two panel-beating relatives, and living in the absolute center of the British motor industry, he couldn’t help but be infected by the excitement of motoring. But it wasn’t easy. An application to Armstrong-Siddeley failed, he then worked in the Humber engine shops, but finally grabbed an apprenticeship with Armstrong-Siddeley in 1935.

This was one of the city’s most prestigious firms, which inspired the keen young Dewis for life. First as a young trainee test driver, and later in the aircraft engine section (war was imminent, don’t forget), he soon got a local reputation. Dewis loved it all, and would never leave it.

After serving as an air-gunner with the RAF during World War II, he returned to Armstrong-Siddeley, then moved across to Lea-Francis. As a talented driver, he took charge of road test and development work. Even though they had efficient four-cylinder engines, the Lea-Francis car was neither technically advanced nor attractive, so Norman began looking around. It was then that the ‘Coventry-mafia’ swung into action. Jack Ridley (Dewis’s boss at Lea Francis), knew that Jaguar needed a good test driver, who immediately contacted Dewis with an offer. Starting in January 1952, Dewis moved to Browns Lane, which was to be his beloved work place for the next 33 years.

Jaguar needed Dewis. Their latest road cars were fast, their race cars were even faster, yet their long-serving test driver, Joe Sutton, had never lived comfortably at those speeds. So for Dewis, younger and braver, here was a heaven-sent opportunity. Bob Knight managed the department, Sutton soon retired, and Dewis did most of the test driving. These were the days when Jaguar was refining the C-Type race car (Bob Knight had designed the chassis, Malcolm Sayer the aerodynamic style), and when the very first Dunlop disc brakes were being tested. Dewis, seemingly without fear, got to know Dunlop well, and trusted what they were doing: “I became quite used to going off [the road…] with the C-Type when we were doing the disc-brake development. It was nothing to be coming down the main straight…into the tight bend at the bottom to find the pedal just go straight to the floor. So I became accustomed to running off the circuit and back on again.” Trust was certainly needed, for early disc brakes overheated, burst their seals, boiled their fluids, and grabbed – sometimes independently, sometimes in combination!

Months later, Dewis made his first appearance in a race car—sitting alongside Stirling Moss throughout the 1952 Mille Miglia, in a disc-braked C-Type. Retirement from the race followed a crash, which damaged the steering rack, but the brakes were fine.

Dewis also got all the high-speed delivery jobs. If a race car had to be driven across Europe to the start of an event (transporters were still a rarity in those days), Norman got the job. If a car had retired broken, then patched up, and needed to be nursed back home, guess who flew out to collect it?

Even so, there were some escapades he would rather not have experienced. In 1953 Jaguar used the Belgian Jabbeke highway (it’s now part of the motorway from Brussels to the coast at Ostend) to set speed record with race-tuned and streamlined XK120, equipped with a tiny bubble-top canopy, and Dewis at the helm. The performance was fine—no XK120 ever again approached the 172.412 mph it achieved—but Dewis was nearly asphyxiated along the way. Body sealing was so good, and the canopy so restricting, that Dewis almost exhausted the available oxygen in a few minutes: “I thought, God, I can’t open it [the canopy], and to push my fist through it would ruin everything, so somehow I got back. When they opened it I was near to collapsing, and they said I looked like a tomato!”

Taming the D-Type

When the legendary D-Type came along Dewis took over all the high-speed testing and development. Although there were still occasions when he went out in a Mark VIIM, a 2.4 or 3.4-litre saloon, he spent much time pounding away, either at MIRA, where there was a 3-mile high-speed banked circuit, or up and down the two-mile runway of RAF Gaydon. This explains why Dewis gave the very first D-Type (OVC 501) its shake-down runs in 1954, but at the Le Mans test runs which followed in May he had to watch Tony Rolt and Peter Walker doing the driving.

He was at Le Mans in 1954 when the D-Types competed, and although nominated as a reserve driver, he did not actually drive.

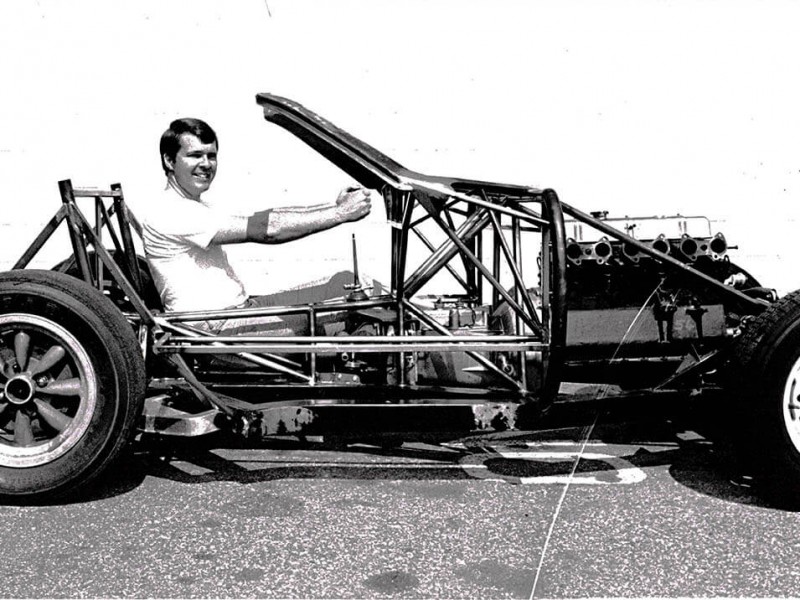

The D-Type race car, in which Dewis was closely involved, used this multi-tube frame as its primary chassis.

Sometimes, though, he got the plum ‘publicity’ jobs, one of which was to demonstrate the Le Mans D-Type at the Brighton Speed Trials, on the promenade of Britain’s south coast town. This involved Dewis taking the car home from work on the Saturday morning, parking it in his Coventry driveway (yes, that is how things were done in the 1950s), and motoring sedately down to Brighton the following morning. Except that his alarm clock failed. He got up late and had to make a flat-out dash south. Starting up a D-Type at the racetrack is one thing, but starting it up Sunday morning on a peaceful street is another. The following day, they say, Dewis had to apologize personally to every one of his neighbors for the commotion. That was the occasion, Dewis once admitted, when he broke his own personal record for the Coventry to Central London trip, in the days before any motorways were built.

Finally, and in spite of Sir William’s reservations, Dewis got his ‘works’ drive, sharing a new D-Type with Don Beauman at Le Mans in June, 1955. In a race that will forever be tainted by the tragedy of Pierre Levegh’s Mercedes-Benz 300SLR ploughing into the grandstand opposite the pits, Dewis and Beauman got the D-Type up into fourth place, overall, before Beauman put the car off into the sand.

Weeks later Dewis shared Jack Broadhead’s privately-owned D-Type with Bob Berry (another Jaguar employee), to take fifth place in the Goodwood Nine-Hour race, but at the end of a traumatic season which included deaths in the Tourist Trophy race held in northern Ireland Sir William put his foot down and ended his racing career.

There was still, however, much high-speed motoring to be done at Jaguar, for the very first E-Type prototype was built in 1957, and the one-off racing prototype E2A, soon followed. For the next few years, Dewis was submerged in E-Type and XJ6 road-car development, including spending many hours in a tatty-looking Mark X, which just happened to have a prototype V12 engine under the bonnet. Even so, there was often the chance to work on the very specialised lightweight E-Type race cars which Jaguar developed for drivers such as Graham Hill and Roy Salvadori to race against the latest Ferrari 250GTOs.

Then, in secret, came work on the most amazing Jaguar prototype of all time—the mid-engined XJ13. First tested in 1967, this 500bhp/5-litre V12 race car was meant to herald a Jaguar return to Le Mans. Dewis, naturally, made the first test runs at MIRA, usually during weekends when no one was looking.

By mid-year the plucky Dewis had already lapped the banked circuit averaging 160mph—with top speeds of more than 180mph—and had also sampled a Ford GT40, which Jaguar had ‘borrowed’ for comparison. Even so, Jaguar swiftly sidelined the XJ13, putting it away under a dust sheet until 1971, when it was decided to show it at the launch of the new V12-engined Series III E-Type.

Once again, Dewis was asked to take the XJ13 around the MIRA banking, for the benefit of a film crew: “I was half way round the banking with the power full on, probably doing about 130mph, when I felt a sudden lurch from the back end. This turned me straight into the safety fence at the top, I grabbed the wheel, pulled it down from there, and I did a series of gyrations across the track, heading towards the infield…I feel sure one magnesium alloy wheel had collapsed through fatigue.” Having hit a marker barrel and rolled over several times, the totally wrecked car ended up in a field, right way up, with Dewis still on board. He never could explain how he survived, but happily pointed out that in all his career he never broke a bone in more than a million miles of testing. Thereafter, and for the rest of his professional life, he stayed away from racing cars.

To the end, when he moved to live close to Ludlow, Dewis was still a formidably fast driver. Having bought his retirement home well before retirement day, he got to know the main A5 road very well indeed—along with those who sometimes witnessed him passing them by. MM

'Norman Dewis: A Jaguar Legend' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!