By Peter Brock

In the late 1960s, RW “Kas” Kastner was British Leyland’s visionary Director of Motorsports for the entire United States in the final days of the SCCA’s rather blurred concept of “amateur” road racing in America. From their small office in Westport, Connecticut, the elitist officers of the SCCA were trying to maintain an Olympian ideal of the sport for their mostly northeastern constituency. Kastner, based far to the west in Los Angeles, in addition to his task of developing parts and tuning secrets for all Triumph racers, was in the center of a political and philosophical revolution regarding the future of sports car racing in America. He was having a difficult time convincing his directors in England that Triumph’s future in America was facing an economic reality that required greater success on the track if it was to continue in the increasingly competitive sports car market.

While most sports car activity in the US had been under the control of the SCCA since the late ’40s, a fast growing “outlaw” group of competition oriented enthusiasts in Southern California, made up of racers, garage owners, hot-rodders, car dealers, and a scattering of performance industry leaders, banded together to form the Los Angeles based California Sports Car Club. Their goal was to make road racing better and safer for drivers, course workers and spectators, but also to tap the full potential of the sport by encouraging the development of specially designed racing circuits, like Riverside Raceway, specifically to meet the growing enthusiastic support of road racing. The “Cal Club,” as it was known locally, was the antithesis of everything SCCA. Even though the Westport pharaohs did have a local Southern California Region, there was little support in the local car community for its tame TSD “rally” events and simple gymkhana type autocrosses. Cal Clubbers were essentially hard core racers with the business acumen to grow the sport in ways never envisioned in Westport.

This budding transitional era, from amateur to professionalism, was led in part by Triumph’s strong support of its amateur racers but also by similar programs being backed by Porsche and Datsun (Nissan), all working to insure that each manufacturer had top level teams capable of qualifying for the SCCA’s prestigious National Championships, which were being held alternately at major circuits in various parts of the United States.

At the peak of this inaugural amateur era, just prior to the advent of real “professional racing,” like the SCCA’s finally pro- sanctioned CanAm and TransAm series, the sport’s national and media focus was on the few manufacturer backed teams in the SCCA’s highly competitive C Production category. Although the sport was still supposed to be “amateur,” Porsche, Triumph, Datsun, and even Toyota for one year, all backed well financed semi-professional teams in those SCCA regions with the highest concentration of serious racers. Triumph, of course, led with its Kastner backed teams on the west coast while Bob Tullius carried the Triumph flag on the east coast out of Falls Church, Virginia. Porsche, with its fleet of potent mid-engined 914-6 roadsters contracted top ex-F1 star Ritchie Ginther to lead its west coast contingent out of San Diego while highly respected American star Bob Holbert did the same on the east coast. Datsun used SCCA veteran Bob Sharp to run their team of 240Zs on the east coast, while my shop, Brock Racing Enterprises (BRE), did the same with two Z-cars in El Segundo in Southern California. Even Carroll Shelby was contracted in 1968 by Toyota to develop and race its new 2000GT coupes for a single season.

With ever increasing sales competition from Europe and Japan, Triumph’s now rather aging TR series roadsters, as fast as they were under Kastner’s keen development program, were obviously nearing the end of their potential. It was here that Kas and I, fierce competitors on track but good friends off, started discussing over dinner one evening our racing futures. In those days, more so than today, success on the track translated to sales on the street, so we saw it as our job to raise the manufacturer’s image with improved quality, performance and appearance. We also realized the media value of racing victories also depended on the quality of the competition. Without the credibility of each marque’s solid performance on track the importance of our own success could be diminished. We felt that a newer, faster, better looking Triumph would improve racing and sales for all, especially in America with the increasing media coverage now being devoted to the highly professional “amateur” racing series in the SCCA C Production class.

Proven with numerous National Championships for Triumph, Kastner’s development of the TR series chassis had given it excellent performance, but the car’s handsome classic English styling limited top end performance as well as some sales appeal on the street. I suggested a new aerodynamically efficient body designed specifically for the existing TR chassis, using Triumph’s new 2.5 liter six cylinder engine, would solve both problems. Having had some recent spectacular success with a similar design concept for Carroll Shelby’s World Championship winning Daytona Cobra Coupes, built on AC’s now ancient Cobra roadster chassis, I knew using a similar concept for Triumph would work. The financial advantage to British Leyland being that the development and manufacturing costs would be minimal, as only new body tooling would be necessary. The existing production TR chassis, engine and running gear were still proving effective.

Since there was no way a one-off hand-built concept could be raced in the SCCA, as the required numbers for official homologation had not been produced, Kas and I focused on the idea of building and running a “production concept” in the Prototype category at the 12 Hours of Sebring in 1968. Since this prestigious international event also had classes for existing production cars, it was expected that a works backed Porsche team (who we considered our major competitor in SCCA) would be running 914-6s set up with their latest racing specs preparing for the following season’s major SCCA events. The target then was to build a one-off “concept” to full street production specs, using a full windscreen, side-windows, interior and all the lights and running gear required for a properly street licensed vehicle, but modified for SCCA “production” racing. In this manner the proposed “production” Triumph could still be compared directly against its real production adversaries even though it wouldn’t be running in their class. Better yet the international exposure of this event would allow British Leyland’s executives to gauge public acceptance of the new design without themselves having to do more than agree to its construction with minimal financial risk.

With Kastner already scheduled for his semi-annual visit to British Leyland’s main office in the UK, he also arranged to stop over for a few hours in New York City to visit with Leon Mandel, the editor of Car and Driver magazine. In preparation to divulge his plan, Kas took with him a drawing I had hastily sketched of the car along with the Sebring race proposal. Mandel, enthused by our outrageous plan quickly agreed to allot the cover of Car and Driver, complete with a multi-page story, on the concept. That “gift” alone was worth thousands in positive credibility for Triumph’s future in the American market. With the sketch and the added promise of Car and Driver’s coverage, Kastner headed on to England and there eventually convinced a highly conservative B/L management team that his plan had serious merit. However, with British Leyland’s financial future in doubt there was little if any monetary aide available. But a very convincing Kastner was still able to extract a few thousand Pounds toward the project; hardly the full amount needed to build the car but it was a start. Most of the required funding would eventually be extracted from our own annual competition budgets.

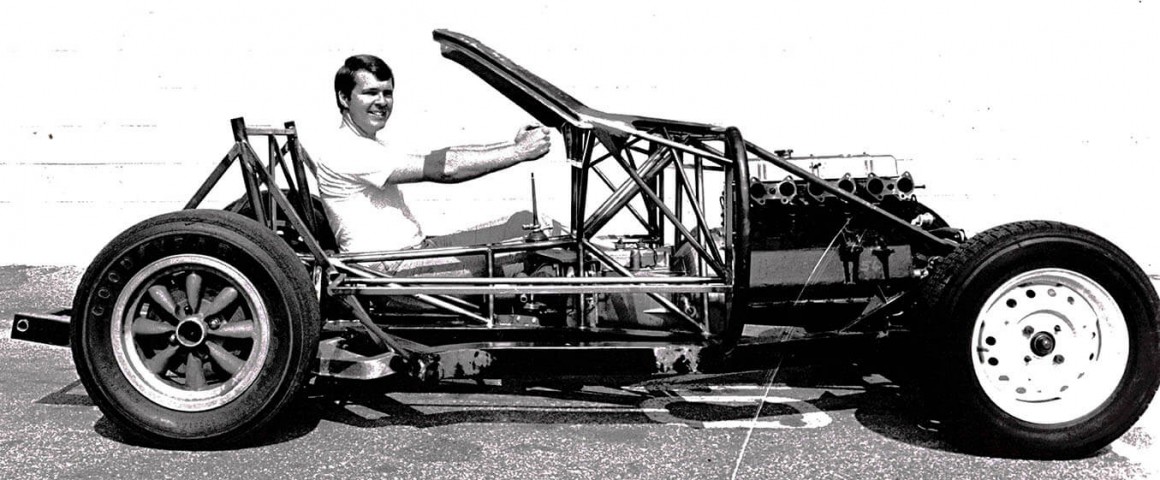

Upon Kas’ return, he and I met again to reassess the program. Without the funds needed to build a coupe as I had originally planned (so that the car could run at Le Mans later in the year if it was successful at Sebring), it was necessary to scale back to a simpler roadster version and concentrate on Sebring. Kastner pulled a bare TR4 chassis and new 2.5 liter six cylinder engine from his warehouse and turned it over to my shop to do the necessary modifications to fit the new body. All suspension and engine modifications would be accomplished on its return to Kastner Engineering after the car’s main components had been relocated. A generous weight distribution improvement was accomplished by repositioning the seating, engine and transmission as far rearward as possible within the stock frame and then fabricating a lightweight tubular sub-structure around the new cockpit dimensions to support the new windscreen, doors and instrument panel.

What began as a drawing was then sculpted to quarter scale in clay. My original aero-efficient roof I quickly scraped away, creating a high-backed roadster. A full-size wooden buck was built off the scale plans and sent to California Metal Shaping in downtown Los Angeles for the main alloy panels to be formed. Cal Metal had long been a fabrication staple of So-Cal’s best race car builders. Using large industrial power-hammers left over from WWII aircraft manufacturers, Cal Metal made raw body panels for everything from Indy roadsters to Bonneville streamliners. Once these raw panels were completed and Kastner’s frame had been properly tuned to competition spec, the combination of components was taken to the small fabrication shop of Don Borth and Red Rose who had worked extensively with me when building the Daytona Cobra Coupes at Shelby American. Their fabrication skills created the final form to exactly match my clay model.

Without the necessary budget to build special wheels for the new car, I acquired some suitable mag wheels left over from the construction of one of Jim Hall’s early Chaparral specials. This was just one of the detail compromises made to finish the car in time for Sebring.

Without the trailer load of spares normally required for such an endeavor, both Kas and I knew we’d be gambling with fate for the 12 Hours, but at least the car was complete and ready to run. I took the freshly painted TR250K to the desert for some early morning photography for the Car and Driver cover shot and returned it to Kastner for final detail work. Without adequate time or money for testing and development on track, Kastner loaded the car and sent it off to Sebring for one morning’s compressed on-track testing before the start. Kastner had selected the country’s two top Triumph drivers, Jim Dittemore and Bob Tullius, to drive the K-car in the 12 Hours.

Testing on the fast but rough Sebring circuit soon proved the value of the car’s adjustable rear spoiler. When Dittemore had been unable to make it through a set of long fast sweepers without lifting, the spoiler was set to a slightly higher angle and with the improved downforce he easily went through flat out. Had he actually been in the class for 2.5 liter production cars, his time would have been a lap record. On track aero-tuning was still an unfamiliar concept in those days, and the TR250K was years ahead of its time.

In the first couple hours of the race the TR250K easily out-performed its target speeds with laps faster than most of the works-backed Porsche team cars. Had the car won its class against its German rivals its future may have been a bright one, but it was not to be. One of the mag wheels failed, ripping away part of the car’s braking system. With no spares to make the repair it was a disappointing DNF. Still, as the response to the Car and Driver article proved, it was resounding aesthetic achievement.

In the end it wasn’t that the directors at British Leyland were unimpressed with the car’s appearance or its performance at Sebring. It was simply that such a radical new design from “outside,” especially from America, was simply misunderstood. Even the logic of building a faster, better-looking TR that was already underway, for far less than an all-new car, simply had no support from anyone within British Leyland. No one in management had any understanding of what was really needed to compete in their prime market, America.

Today the TR250K is owned by Bill Hart of Redmond, Washington, who graciously allows it out on track once every two years to be expertly driven and displayed by tuner Tony Garmey who also maintains and preps it for racing. Kas and I thank them both for bringing it to Buttonwillow Raceway last year for the 2019 Kastner Cup. MM

See the TR250K in action, and hear more of the story of its development from Kas Kastner and Peter Brock at: classicmotorfilms.com/tr250K

'The Triumph That Could Have Been' has 1 comment

April 19, 2020 @ 6:00 am Dave D

Thanks for a great article!

If my father had allowed me to buy that TR4 IRS back in 1970, I might’ve been a Triumph guy. A few years later I traded a VW Karmen Ghia for a 1959 MGA, (I’m sure my Father thought I was nuts) and the rest is all MG.

That said, the TR250K is a beautiful car. I would have liked to have seen it as a Coupe as well. It’s a shame they didn’t attempt to race it more. Another set of properly fit wheels and more spares is probably all it would’ve taken. However, I’m guessing that because it was a demo concept, and had no chance of winning in the class it had to run, it was pointless to continue.

My opinion is that had it gone into production, it would have sold poorly. I base it on 5 years later the TR7 came out with styling far ahead of it’s time, is still a good looking car today, but didn’t sell well enough. Since it came out in 1974 I’ve pointed to BL not coming out with a roadster at it’s launch.

The most telling part of the article to me was “No one in management had any understanding of what was really needed to compete in their prime market, America.” BL’s largest market and they didn’t know how to sell cars here, with there’s no evidence that shows they wanted to. How does one run a major corporation and not know the major market? It’s nearly unfathomable, because if BL had a competent upper management team, it’s hard to say how far they could’ve gone, and not hard to believe that BL would still be building new MG and Triumph cars today.