By Graham Robson

Okay, admit it, and be proud of it—many of you out there own cars built around the time when Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II came to the throne in 1952, the year in which the British Motor Corporation (BMC) was founded. When the new Queen walked down the steps of her aircraft at London’s Heathrow Airport, she was starting what the British press called a ‘New Elizabethan Era’.

Looking back sixty-five years shows us just how completely the British car scene has changed. Not only was Britain’s largest carmaker, BMC Austin, still British owned, but it dominated the market. It was a time when Britain’s carmakers out-sold everyone except the Americans. Surely this would last indefinitely. Or could it?

Post-war Recovery

By 1952, Britain’s motor industry still had a colossal order bank, and a long waiting list for new cars. My father ordered his new Ford in 1948, but it was not delivered until 1953. Britain’s factories produced only 219,162 cars in 1946, and 522,515 in 1950. In 1952, the first ‘Elizabethan year’, production dropped back to 448,000, of which 308,942 were sent overseas.

By then, the aftermath of war was nearly forgotten, and normal life was returning. Unhappily, British carmakers still wanted to make models that appealed to them rather than to the customer. Does that explain why there were British cars that overheated in American summers? Where the heater didn’t work well in winter? Where you needed a tame mechanic in the garage to keep it on the road?

In those days, of course, Government ministers encouraged carmakers to revert to a single-model policy. One wonders why? Once the Model T had been killed off, this hadn’t worked for Ford-USA, and for sure it wasn’t going to work in Britain. Accordingly, most carmakers ignored the message and started widening their ranges as fast as they could.

Britain’s League Table

In 1951, there were still 34 makes of British cars, of which the ‘Big Six’ dominated the numbers game. Two groupings—BMC (Austin, Morris, MG, Riley and Wolseley) and Rootes (Hillman, Humber and Sunbeam-Talbot)—took centre stage. Ford sold more cars than Vauxhall, while Standard-Triumph brought up the tail.

Leonard Lord

The balance was provided by a series of glamorous independents, of which Bentley, Daimler, Jaguar, Rolls-Royce and Rover made most headlines. Even so, it was marques like Allard, Aston Martin, Frazer Nash, Healey and Morgan, which produced interesting and sporty cars, the type which many still love and restore today.

Now, though, it is time to recall how BMC was formed, and how it became the massive grouping which came to produce so many MGs, and Austin-Healeys, almost all of which went to the export market, many of them finding homes in North America.

Up until then, the ‘founding fathers’—Austin and Nuffield (which meant Morris, MG, Riley and Wolseley)—were fiercely and proudly independent of each other. Herbert Austin had founded his company in 1905, saw it grow to the largest British car maker by the late 1930s, and to begin looking round for more conquest in the post-war years. Nuffield, on the other hand, had been set up as Morris Motors in 1913, invented MG in 1924, then bought up Wolseley in 1927 and Riley in 1938. By then its founder, William Morris, had been raised to the British peerage as Lord Nuffield, and the grouping therefore became the Nuffield Organisation.

By 1951, however, both companies needed to merge to underpin their plans for further expansion. Austin built 132,557 cars that year, and Nuffield 110,654, and although both were profitable, there wasn’t enough in their ‘war chests’ to finance huge expansion. Accordingly, Austin’s chairman, Leonard Lord, made the first approach to promote a merger, but as he and Lord Nuffield could then be described as the ‘Best of Enemies’ (Lord had worked for him in the 1930s and neither had enjoyed the experience), he was originally re-buffed.

Months later, Nuffield, who was by then an old and physically fading personality, thought again, and gave in with ill grace, the result being that BMC was officially formed on 31 March 1952. From that moment, Leonard Lord became CEO and within months Nuffield was persuaded to retire completely, leaving Lord as chairman, too.

The corporate surgery began at once, for although both Austin (with the A30) and Morris (with the Minor) were making hugely popular small cars, their middle-size and larger cars all needed rejuvenation. Not only that, but Nuffield’s MG (the TD, at the time) was an appealing sports car, it was technically obsolescent, while Austin produced nothing more exciting than the awfully ugly A90 Atlantic. Len Lord’s plans to impress the North American sports car market could not be achieved until he had a new MG—which appeared as the MGA in 1955—and invented another brand, the Austin-Healey of 1953.

Quality and Character

On the other hand, there was still some motoring class to be had. If you were rich, you looked no further than Bentley, Daimler and Rolls-Royce, but if you were middle-class you could order an Alvis 3-litre, an Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire, a Bristol 401, a Humber Hawk, a Jaguar Mk VII, a Jowett Javelin, a Riley RMA 2 ½-litre, a Rover 75, a Sunbeam-Talbot 90, or a Triumph Renown: some never reached the USA, of course.

You also got wooden dashboards, leather seating, rakish styling, and individual engineering. But, sad to say, some of these companies would not survive for long (Jowett disappeared within a year, Armstrong-Siddeley in 1960, and Alvis in 1967) but this was the time when they were still enjoying a reputation.

Jaguar, of course, was on a high, and getting higher. With the TR2 on the way, Triumph would soon come to mean a whole lot more to North America than it did in 1952. And Rover would hang on so well that its name would eventually go to the country’s last all-British combine tractor.

Popular Sports Cars

It was Britain’s sports cars which made the most news in 1952—especially in North America—and BMC was responsible for most of them.

The variety was amazing: from the sleek, 120mph Jaguar XK120, to the creaky old Morgan Plus 4, the cheap and cheerful MG TD to the expensive but appealing Healeys, and from Cadillac-engined Allards to hand-built Bristol-engined Frazer Nashes. And I haven’t even mentioned the Aston Martin DB2, the HRG, or the Jowett Jupiter.

British sports cars controlled the market (no competition from Japan, just yet). There was tradition, style, racing success, and there was sentiment behind this. America’s love of British sports cars, they say, was forged during World War II, when thousands of US Army and USAAF personnel were based in the UK, and discovered the three greats: British pubs, British girls, and British sports cars!

There was, indeed, something about British sports cars that could not be replicated, nor learned in the classroom. Other countries would try to match our popular-price models, but had little success—not, that is, until the Datsun 240Z in the 1970s.

As far as North America was concerned, it was the quaint MG TC which started a trend in the late 1940s, and the independently-sprung TD of 1950 built on that success. But it was Jaguar’s amazing XK120 which really caused a sensation. Even in 1952, when deliveries had been going on for three years, to own an XK still seemed like an impossible dream for so many enthusiasts.

Morris assembly plant at Cowley, circa 1930s. The top building is the original Pressed Steel Co. factory.

It wasn’t just the appeal of the silky-smooth XK engine—the world’s first-ever series-production twin-cam, by the way—and it wasn’t only the seduction of that sleek two-seater style. There was also the character, the sound, and the still-unbelievable ability of a road car to reach 120mph in a straight line. The fact that Jaguar had just gone into sports car racing with the special C-Type, and won the Le Mans 24-Hour race at the first attempt with that car, confirmed the Jaguar legend.

Behind Jaguar and the MG, too, there were several other worthy machines. Allards—especially the J2X types which got Cadillac V8 engines—were crudely engineered but effective, Jowett Jupiters looked better than they actually were, while Aston Martin’s DB2 was the first of another family of fine, twin-cam engined sports coupes.

For lovers of sporty motoring, 1952 was already a great time to be around—and that was before that famous day at London’s Earls Court Motor Show in October, when Donald Healey and Triumph both showed their latest prototypes. Although the Triumph was still undeveloped and needed a rear-end re-style before TR2 deliveries began, the Healey 100 only needed an alliance with BMC to make the 100 BN1 famous.

Here was Britain’s sporting future. Even so, for MG, London’s 1952 Motor Show must have been a nightmare. Not one, but two important new sports cars broke cover – and both of them were set to hit hard at the TD’s cosy marketplace. It was a revolution in looks, performance, and value for money—for Triumph’s new TR2 and (at a higher price) Austin-Healey’s 100 were about to render the old-style MG completely obsolete.

Just think about it. In 1952 the TD had no serious competition, but it was already old-fashioned. The only other small-engined British sports cars were the archaic old HRGs and Singer Roadsters. Along with the Jowett Jupiter, these were all slow and expensive. MG, its TD’s styling rooted way back in the 1930s, was smug—and it showed.

Then came October, and the promise of two smart new sports cars which would soon blow the 80mph TD into the weeds. By mid-1953, not only would Triumph have the 100mph TR2 on sale at similar price levels, but the larger-engined Austin-Healey 100 seemed to offer so much more style and performance. The TR2 and the Austin-Healey 100 represented a step-change in British sports cars—they looked modern, they were a full 20mph faster than the TD, and they were comfortable too. When it rained, the cabins stayed dry—and you could also buy removable hardtops. MG never offered either.

Until the MGA arrived three years later, this meant that MG would struggle, but for Austin-Healey and Triumph, the battle was only just starting. It would not be resolved for nearly thirty years. In the meantime, the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s would be an exciting time for open-top fanatics.

Graham Robson is a prolific motoring historian, who started his working life as a design engineer, got involved in rallying as a hobby, started writing about motor sport soon after that, and is now one of motoring’s most published authors. Graham was inducted into the British Sports Car Hall of Fame this year. We are honored to feature more of Graham’s writing in upcoming issues of Moss Motoring.

Captions/Identification

M1) The MG TC

M2) MG TC assembly at Abingdon

M3) MG TD

M4) Morris Minor – 1949

M5) [Morris Cowley factory 1930s] Morris Motors before BMC

M6) [Austin A40 Sports] A40 Sports – the car that gave way to the Austin-Healey 100

M7) [Austin 35 Drop head] A35 ‘sports’ car proposal – thankfully cancelled

M8) Leonard Lord, chairman of BMC

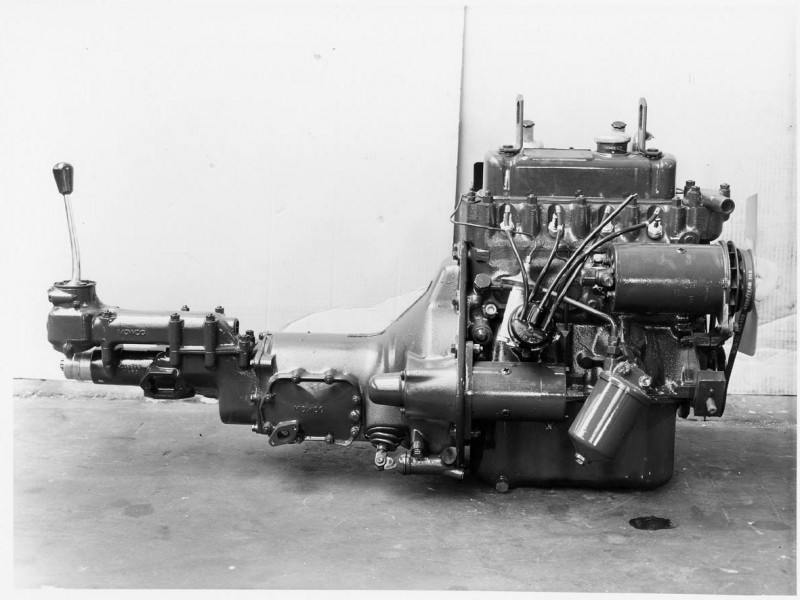

M9) A-Series engine

M10) Austin-Healey 100 assembly, Longbridge 1953

'The Birth of BMC: Sports cars for the masses' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!